Coffee goes through many hands and places. In this journal entry, we’ll briefly show you the typical journey of most of our green coffee purchases, and other considerations that come along that trip. (This article originally appeared in our 2019/20 Impact Report).

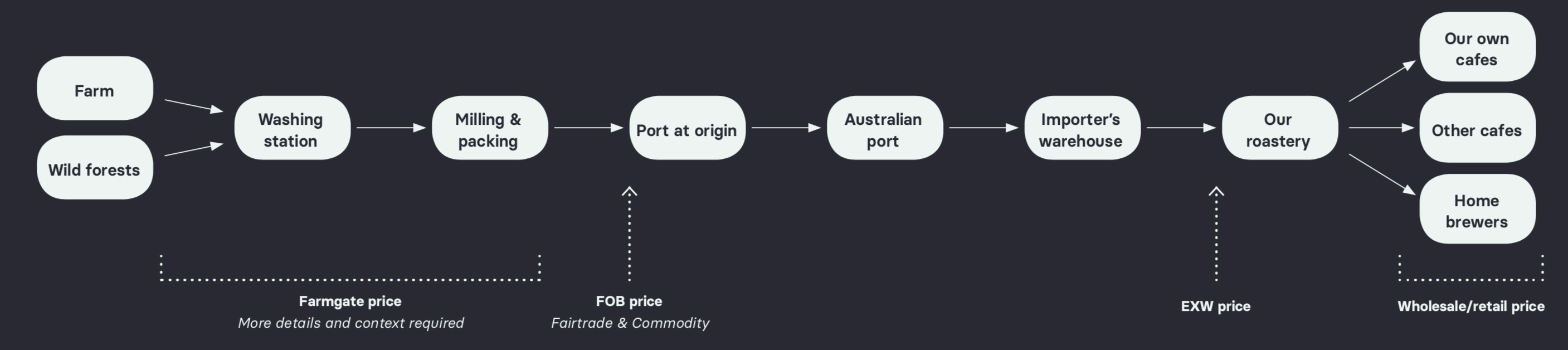

The diagram below represents the basic stages; however, it’s not always a simple formula and it can (and generally does) feature variations:

Click on the image for fullscreen

IMPORTERS SOURCE, MANAGE AND SHIP THE BEANS TO OUR WAREHOUSE

We’re fortunate to work with several importing companies that bring unique coffees to (literally) our doorstep. They take care of sourcing coffees, building relationships with producers, deal with the import/export logistics, store the coffee in conditioned warehouses and finally deliver the beans straight to our roasting space.

Not having to worry about all the intricacies of importing goods from numerous countries around the world lets us focus in what we do best: selecting, roasting, brewing and serving the coffees we dream of drinking every single day.

A truck in a road near the coffee-producing area of Jimma, Ethiopia

TRANSPARENCY: NUMBERS ALONE ARE NOT GREAT STORYTELLERS

If you are deep into the specialty coffee or sustainability world, you certainly must be aware of the industry push for transparency and traceability. Prices are generally included in the conversation as part of a critical asset; however, merely sharing those values as such, when and if not attaching more details of its context, may not be the ultimate solution.

The limitations of using numeric values only become obvious when we read Aislinn Cullen’s reply when we asked from Melbourne Coffee Merchants for farmgate prices, and other metrics, of our green coffee purchases through them:

“Rwandan farmers are paid for fresh cherry on delivery to the coffee washing station, based on a market rate per kilogram set by the Rwandan government at the beginning of the coffee harvest. Farmers who are members of quality- focused cooperatives like Dukunde Kawa [e.g. Marie Bedabasingwa, purchased during FY 19/20] receive a higher rate for their fresh cherry. They also receive a second payment after the season, which is worked out according to the premiums the coffee attracted due to its quality and market competition.

In Bolivia, most coffee producers deliver dried coffee parchment, which has been processed by the farmer using their own equipment. Compared to Rwanda, the farmgate price per kg will be higher because the farmer has assumed the inherent loss and risk of processing the coffee. However, the final product may be of a more inconsistent or lower quality because the equipment and processing standards are not as regulated on a small farm as they are at a centralised washing station.

Julio, Lucio and Pedro [also purchased by us] are all members of the Sol de la Mañana program and deliver their fresh cherry to (the exporter) Agricafé’s mill, where it is processed and dried with exacting standards. They initially receive a lower payment for their cherry than producers selling dried parchment, but they also take an additional payment for their coffee after it has sold. On top of processing the coffee to achieve the highest quality, Agricafé also markets the coffees to specialty-focused buyers and can achieve high premiums on behalf of the producers.”

LOST WITH ALL THE COFFEE LINGO? YOU’RE NOT ALONE

Head to our journal for key definitions of the specialty coffee world jargon.